WHAT ACTUALLY MAKES A PLANT INVASIVE?

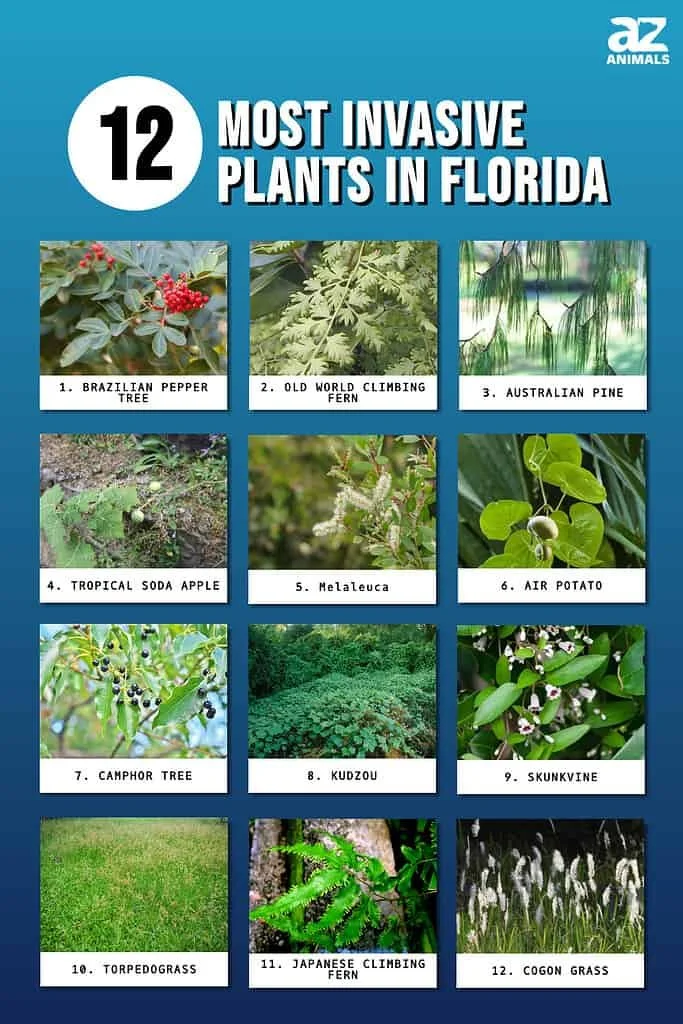

Our beautiful state of Florida boasts a rank of 3rd in the US for its flora diversity, with about 4,700 native and naturalized species. Surprisingly, about 1,500 of those are all non-native plants. What’s even more surprising? According to the Florida Invasive Species Council, only about 11% of those 1,500 are problematic, or categorized as invasive. So yes, it’s true that when we’re talking about the invasive plants problem here in Florida, we’re generally only talking about approximately 165 species that are wreaking all the havoc requiring some kind of management or control.

In a previous blog article, we mentioned that invasive plants are those introduced by humans, found outside their native range that can cause harm to humans, the environment or the economy. But this definition really only addresses the effects of invasives. The million-dollar question really is “What actually makes a plant invasive?” Is it flower color? No. Is it leaf shape? Also, no. Is it where they came from? Not entirely. It’s actually quite tricky to predict plant invasiveness! In addition to some unique plant characteristics, there are other variables that can contribute to invasiveness such as the interaction with other species, the environment and climate conditions. These variables explain why a plant that’s invasive in Florida is not invasive in say, Montana or Nevada. Thankfully though, there is good consensus in the scientific community on the general characteristics that make a plant species more likely become invasive.

Image credit: Michael Keys

In this article, we’ll cover these general traits that set invasive plants apart as natural troublemakers in our ecosystems. We’ll also arm you with some fantastic resources available to determine if the plant you desire in your yard is perhaps headed for invasiveness in the near or distant future.

Reproductive Characteristics

Why limit yourself to one way when you can do something in a variety of ways? Many invasive plants would agree as they tend to have multiple aces up their sleeve when it comes to reproducing. Reproduction by both sexual and asexual methods give invasive plants multiple ways to keep spreading and push out native species. Look no further than the hybrid “mother of millions” or Kalanchoe x houghtonii, to see this in action. This succulent plant can reproduce via pollination and seed production, but it additionally creates “plantlets” along its leaf margins that when shed, give rise to a new plant. And yes, one plant can produce thousands or even millions of these clonal offspring!

A) each plantlet along leaf margin creates a new plant that will grow literally anywhere B) even on a roof C) don’t be fooled by pretty flowers D) close-up of enemy E) leaf detail

Now, there are those invasive plants that reproduce mainly through one method such as pollination. Even so, they do this exceedingly better than their surrounding natives by setting high amounts of highly viable seed.

Rose natal grass, or Melinis repens, is an invasive clumping grass displaying this by setting massive amounts of wind dispersed seeds at an estimated >90% viability! It’s easy to see how quickly invasive plants can spread and get out of control in just about any environment.

Adaptability

Another key trait of invasive plants is their ability to adapt to a wide range of environmental conditions. While there is much more research to be done in this area to predict invasiveness, scientists have a hunch that invasive plants may exhibit more “phenotype plasticity” than native counterparts.

This is a fancy way of saying that a single species has the ability to change their physical traits, according to their environment. Some invasives may also exhibit more genetic differentiation, allowing them to find a variety of habitats suitable for their survival. Sounds like sci-fi, but this natural kind of shape shifting is very much real!

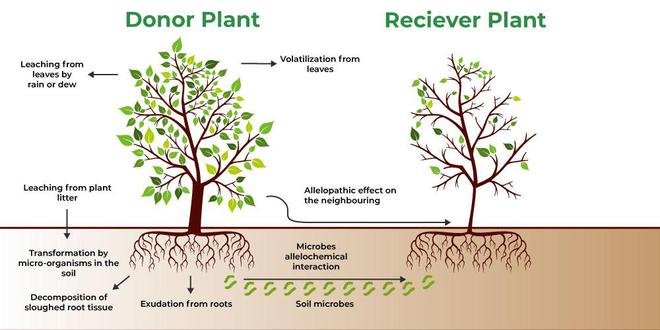

Allelopathy

Some of us may have been taught to never plant a black walnut tree in our garden because it will kill any other plants nearby. While the jury is still out on whether this particular scenario is true, it does bring up an actual characteristic of some invasive plants, and that’s allelopathy. Allelopathy is the ability of a plant to produce chemicals that have an effect, beneficial or harmful, on the growth of other plants nearby. In this case, we’re talking about harmful effects.

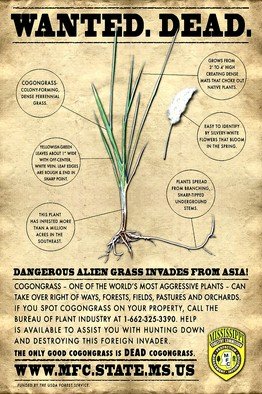

Imperata cylindrica, or cogongrass is infamous for its allelopathic effects. With its ability to exude these chemicals from its plant parts and into the soil, cogongrass suppresses germination and seedling growth of other plants as well as adversely impacting the microbial community in the soil.

Our native plants did not co-evolve with cogongrass, so unfortunately, they have not learned to live with these chemicals either. It’s no wonder when you see cogongrass, you usually only see cogongrass, like in the picture below.

Predators…or Lack Thereof

We’ve saved the best for last here. It’s the one circumstance that brings all these traits we’ve talked about together. As you read this article, you may have thought to yourself, I know plenty of native plants that reproduce both asexually or sexually, or set plenty of seed or even have allelopathic traits, so why aren’t they invasive? By definition, invasive plants are outside their native range, and being far away from home also means being far away from your co-evolved predators!

No predation = invasive plant paradise!

Because of this lack of predation, these plants that have these invasive traits have a recipe for wild, untethered success in their new home. Invasive plants are not kept in check and their populations can therefore rapidly increase, overtaking our native species and affecting the ecosystems they belong to.

Conclusion

We’ve learned that plant invasiveness is not as clear cut as we thought. It takes having some of the nifty traits we discussed, along with being far away from home and your predators to really reach invasive level. And we know that once a plant has leveled up to invasive, it will be a challenge to eradicate. The best way to prevent this is by not introducing that plant to begin with.

Scientists at the UF Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants have developed a few tools to help us do just that. Their plant directory is easily searchable by image or plant name and provides native or invasive status. And for that real invasion prevention ability, look to their predictive assessment tool to see what plants are currently on the radar for likelihood of invasive status in Florida. We know that science is never settled, so visit these every so often to make sure you stay up to date on the latest species.

We are your native plant experts at Wacca Pilatka, so reach out to us if you have questions!